The end of the French and Indian War in 1763 was less than satisfactory for many of the participants, especially the Native American tribes which had been entwined in decades of alliances with British and French forces. After losing their attachment to their longtime French allies in the Great Lakes Region, many Indian tribes were angered by the post-war British policies which aggressive opened white settlement to the Ohio Territory (present day Western Pennsylvania and Ohio), Illinois Country (portions of present day Illinois, Indiana and Michigan) and wider Great Lakes Region (including present day Western New York). British promises to continue the flow of gifts to the tribes in the region were also cut back, further angering the Native peoples who had become dependent on European trade goods over the years.

Feeling duped by British colonial rule, a confederation of more than a dozen tribes rose up in a unified force led by Ottawa leader Pontiac (among other tribal leaders in the region). In the spring of 1763, groups of white settlers and multiple British forts and in the disputed territories were attacked. After the destruction of several smaller forts and an unsuccessful siege at Fort Detroit, another at Fort Pitt also occurred. With a British relief column en route from the east, many of the Indians at Fort Pitt broke off to the meet the British. What resulted was the Battle of Bushy Run on August 5-6, 1763.

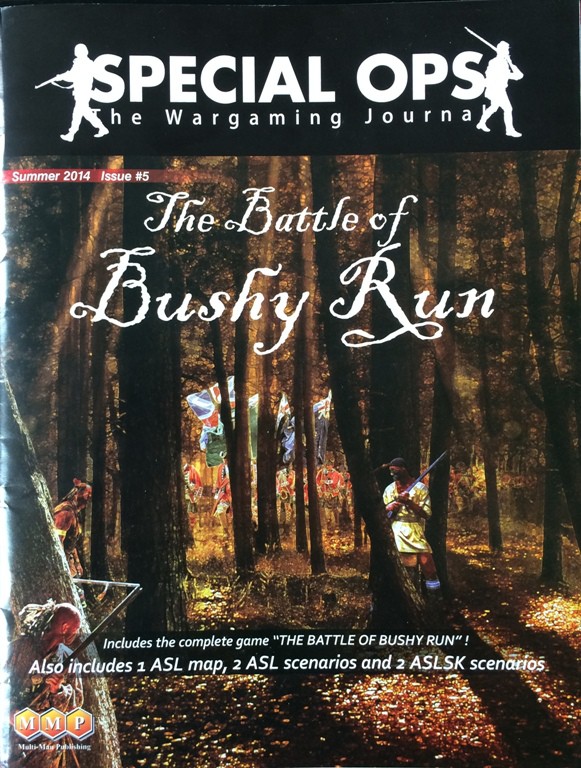

MMP’s Special Ops Issue #5 from September 2014

MMP’s Special Ops Issue #5 from September 2014

Multi-Man Publishing is best known for it’s 20th-century wargames (including the classic Advanced Squad Leader), but the September 2014 issue of their Special Ops magazine contains a nifty little game for the Battle of Bushy Run. Packed into just four pages of rules, 88 cardboard counters and two beautiful maps, MMP’s presentation of the two-day battle in the thick woods of Western Pennsylvania is an incredibly satisfying game.

Indian and British force counters for MMP’s Battle of Bushy Run

Indian and British force counters for MMP’s Battle of Bushy Run

Fire and random turn event markers for MMP’s Battle of Bushy Run

Fire and random turn event markers for MMP’s Battle of Bushy Run

I had a chance to punch and play a new copy of the game this past weekend at Metropolitan Wargamers in Brooklyn, NY. Giving the game it’s first spin with me was a fellow club member who is an instructor at a local college and an expert in 18th-century North American colonial warfare. The playing counters have tidy artwork and are divided into force chips and a variety of other game markers. The British force markers depict the various historic units at the battle with values for strength and movement and step losses. A supply wagon piece provides the path of victory for the British looking to move it off the board and onward to relieve Fort Pitt. Special British scout markers also play as a way to counteract the nature of how the Indian force markers work in the game.

The Indian force markers display the various tribes present at Bushy Run, and each have an identical strength and movement value. Each also has just one step loss, but the way they work in the game does not reward the Indian player for simply standing to fight against the British. Along with the larger game map where the British column begins fully deployed, the Indians deploy on a smaller hidden map. Throughout the game, the Indian player may move their units from one map to the other as they attack, hide or come back concealed. Additionally, some Indian pieces are dummy markers which can add an additional layer of confusion for the British player struggling to see where their enemy are. These simple markers and the double maps helps to create a fantastic simulation of the challenge of the regular British troops in fighting Indians fading in and out of the woods with harassing attacks. Since movement is by the area, each with it’s own defensive equal for both sides, choosing where and when to fight is important for the British and Indians alike.

MMP’s The Battle of Bushy Run in progress

MMP’s The Battle of Bushy Run in progress

Further adding to the unpredictability of the frontier fight is a series of random turn events which can potentially benefit each side in a turn. With the British objective of getting their wagon off the board, the European force must balance choices on when to move, when to engage the surrounding Indian forces and when to stand still to take a round of volley fire. The Indians must capture the wagon using a force which lacks the military superiority of the British, but make up for it in their ability to appear, disappear, move and reappear throughout the battle. Indian casualties can mount quickly under British fire, and the Redcoats can also win by eliminating 14 Indian units.

Our first game resulted in a narrow victory for the British, just wheeling their wagon off the board as the final mass of surviving Indians closed in on all sides. We found the British scouts to be pretty ineffective, but they didn’t hinder the game either. My Indian casualties were high, owing to my more aggressive early game engagement with the British as I worked out how effective the concealed and hidden movement could be. The British also learned some lessons by probably sitting still a turn or two too long, standing and awaiting to fire on the encroaching Indians rather than hustling their column forward from the get-go. For a tiny game depicting a small battle in a largely forgotten period of conflict in Colonial American history, MMP’s The Battle of Bushy Run is a tactical and historical thrill.

![1526266_10202966521378387_8592928619118650316_n[1]](https://brooklynwargaming.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/1526266_10202966521378387_8592928619118650316_n1.jpg?w=600&h=600)

![10294434_10202966516098255_2984079262433725022_n[1]](https://brooklynwargaming.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/10294434_10202966516098255_2984079262433725022_n1.jpg?w=600&h=600)