Editorial note: I wrote this article in May of 2024 on the occasion of the 40th anniversary of Metropolitan Wargamers. The article was originally published by SDHist here.

Background

Metropolitan Wargamers (MWG) was founded in 1984. The club is New York City’s premier and longest-operating gaming organization in the five boroughs with its own dedicated private gaming spaces.

MWG grew out of of the New York Wargamers Association (NYWA), founded in the early 1970s as an affiliation of local Napoleonic miniatures players. By the early 80s, some members of the group split off to form what would become MWG. The club’s first permanent yet short-lived home was on Steinway Street in Queens in a cramped second-story apartment with a couple of small tables and a leaky hole in the roof.

After losing this space, the club moved to its largest space at 20 Broadway in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. In the early 90s, the club was regularly listed in the “Opponents Wanted” section of Avalon Hill’s The General magazine. It touted “its own 2,000 square foot loft for boardgames and miniatures” and “facilities and members to play any game, anytime.”

Occupying the entire second floor of a warehouse, the Broadway space held six tables (plus a poker table) and lines of shelves along the walls holding miniatures, games and an enormous collection of military and history books and magazines. With a dingy couch, a threadbare area rug, peeling linoleum floors, overhead fluorescent lighting, a closet with a cold-water sink and toilet, and an industrial heater mounted to the corner of the ceiling, the Metropolitan Wargamers in Williamsburg reflected the grit of a Brooklyn since largely faded into memory.

For years, a small, dedicated group of about a dozen members struggled to scrape together money to cover rent and keep the club operating. The Broadway building was sold (and subsequently demolished) during the Brooklyn real estate development boom of the early 2000s.,After that, the club moved to its current location in the basement of a four-story, eight-unit 1920 apartment building at 522 Fifth Street in the heart of Park Slope, Brooklyn. (Entrance door pictured above.)

Set-Up

When the club arrived at its new Park Slope home, it was a raw, unused space. About $300 was initially invested in building new tables and shelves. It is still very much a semi-raw basement with a painted concrete floor and brick and stone foundation walls.

We have a front room with three 4’ x 5’ tables, each with multiple racks underneath to hold games in progress, plus a small 4’ x 4’ kitchen style table we salvaged off the street.

Moving down a narrow hall, we have our “monster game” table measuring 8’ x 8’ which plays host to large footprint multi-month games such as World In Flames or Pacific War. The three tables at the rear of the club (two at 5’ x 8’ and one at 5’ x 10’) all have removable tops, handy for hosting months-long games like Empires In Arms or a big RPG dungeon crawl miniatures campaign.

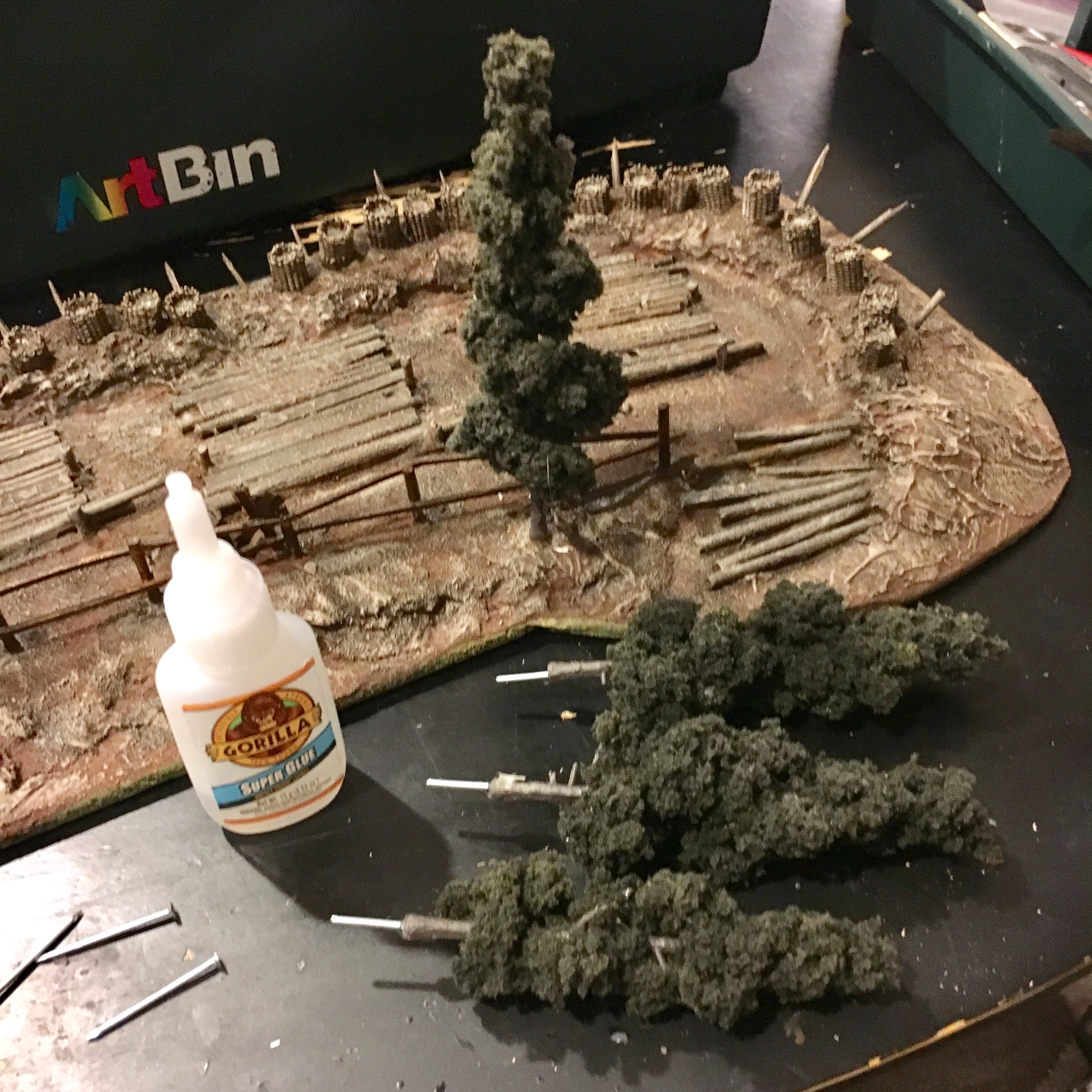

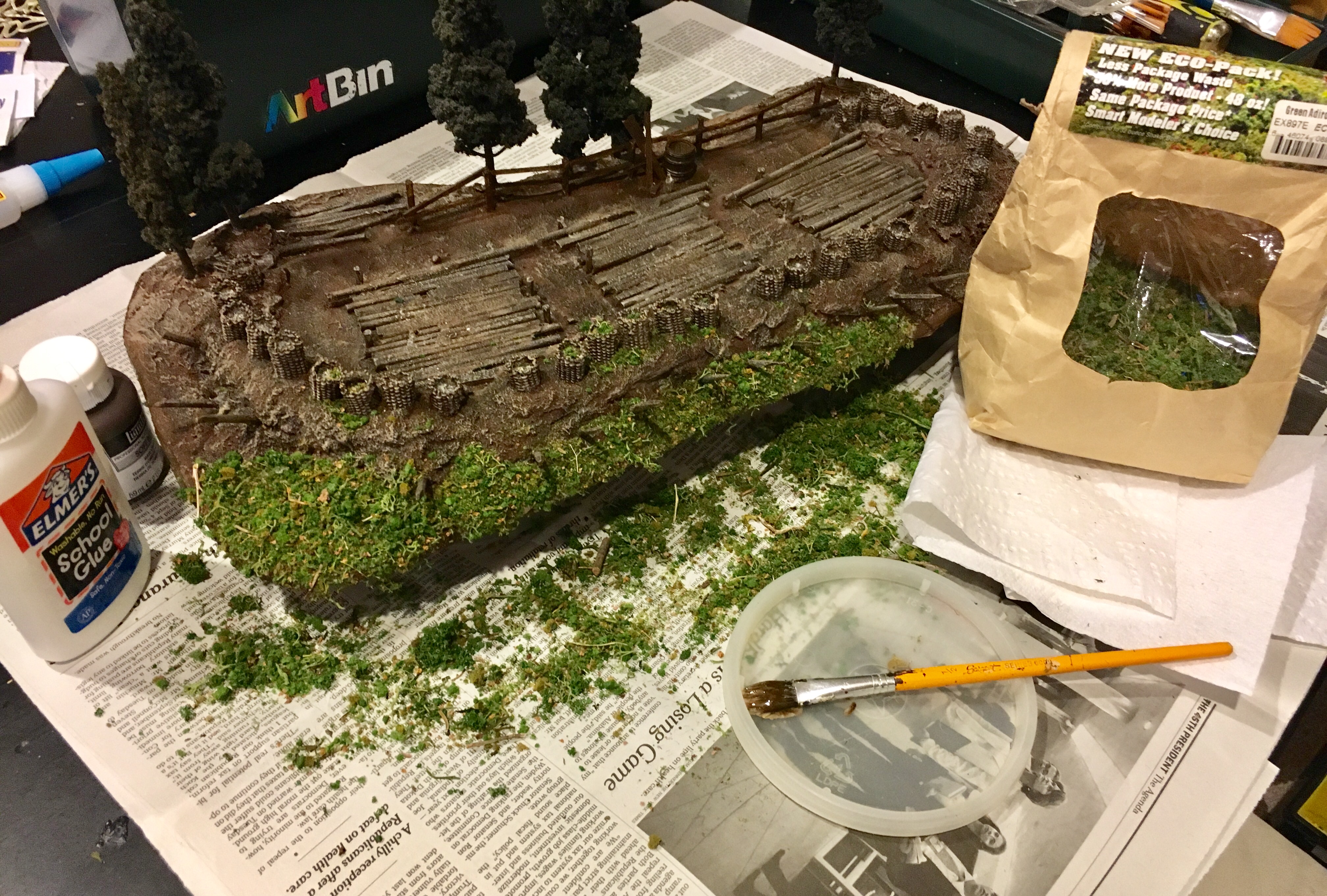

Most uniquely, lifting the covers off two of the tables reveals sand tables for miniatures gaming. World War II miniatures games such as Battleground, Flames of War, O Group and Bolt Action have often been played on these sand tables.

Shelves line the walls of the club, and first-time visitors usually gaze in awe at their contents of hundreds of games and thousands of miniatures. Shelves in the rear hold club-owned terrain – trees, buildings, gaming mats, rivers, roads, hills, and buildings ranging from historical periods to sci-fi and fantasy in multiple scales. A tall rack holds a dozen 4’ x 4’ sheets of plywood where more in-progress games can be stowed. Most of the shelves are rented by members to store personal collections of games and miniatures.

Creature comforts at the club are few. There’s a refrigerator, microwave and coffee maker at the front, a tiny bathroom at the rear, and stairs up and out the back to a small private yard. The yard is used to spray-paint miniatures, and is where we’ll throw food on the grill during warm months.

We finally installed free Wi-Fi within the past two years. Other than that, not a lot has changed since we made the move twenty years ago, and the club remains a bare-bones space solely focused on gaming.

Rules

So how do we manage this gamer’s paradise nestled on a side street in one of the more expensive neighborhoods in Brooklyn? We are fortunate to have a very good relationship with our landlord, who rents us the space for what is far below what he charges for one of his $3200 per month two-bedroom apartments upstairs.

Visitors attend for free as guests their first time at the club, and then pay a weekly fee of $15 whenever they stop by to play again. There’s an option for regular guest players to pay $40 per month for as much gaming as they want, provided they are there with one of our members.

The real magic comes in being voted in as a member of MWG after a 3-month probationary period of paying a monthly fee. With membership comes a set of keys to the club, granting 24/7 access to the space. That said, some visitors pay at the weekly rate for years without becoming members. For gamers largely living in small NYC apartments, the monthly fee of $40 for membership and $20 for a private shelf is a real deal.

Over the past ten years, membership has held steady at around 35 in number, give or take. We each pay our nominal fees, which pays for rent, utilities, cleaning supplies (one member pays no fees and handles all our cleaning and maintenance work) and whatever else comes up like building new shelves or replacing major things like the sink. Because our costs are relatively fixed, we’ve been able to maintain our very reasonable fee structure for years.

Modern gaming cafes in the city typically charge $15 for three to four hours of play, so the club is a bargain for serious gamers looking to clock many hours or even entire days of gaming. Unlike these café spaces, however, we are not open to walk-in traffic.And we don’t keep regular hours, so arrangements to visit are coordinated through an online club message board and via our social media channels on Facebook and Instagram.

Minors aren’t allowed without parents, but we’ve seen a few kids grow up within the club and come back to visit and play. We also don’t rent our space out, although we’ve been asked many times over the years.

Historical Notes

Membership has evolved greatly over the decades at MWG. Our founding members were largely working class first- and second-generation Italian, Irish and Greek New Yorkers who came of age in the 60s, 70s and 80s when New York City was a very different place. Stories abound with some members carrying knives and guns coming to and from the club in Williamsburg.

Today, about half our current membership reflects the modern influx of GenXers and Millennials who flocked to the city since the mid-90s. Our membership ranges in age from mid-20s to mid-80s. We’ve only ever had a few women as members at any given time. We’re fortunate to have many of the old guard around to share our history and that of the hobby with newer arrivals.

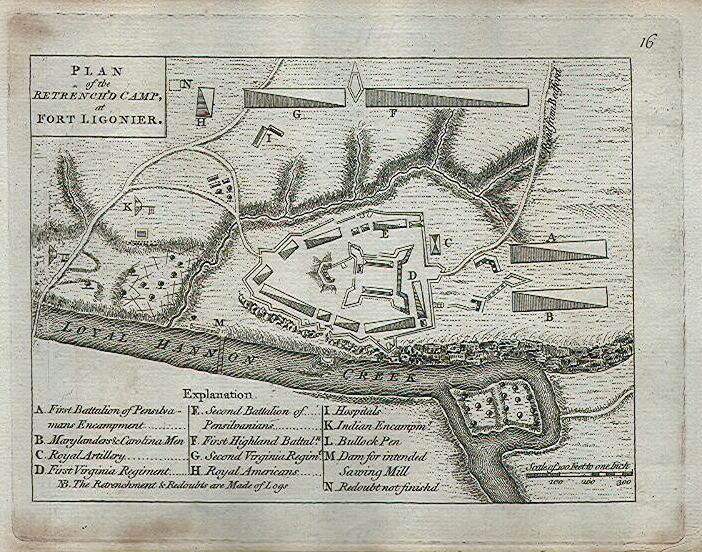

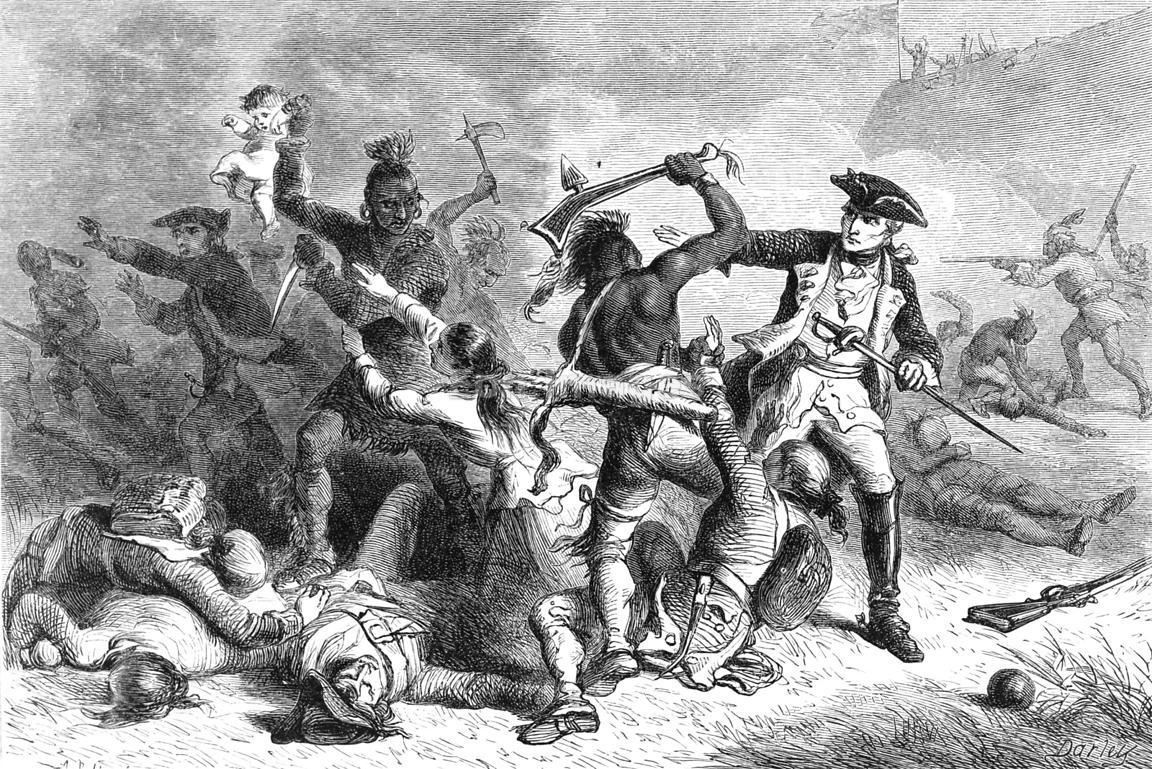

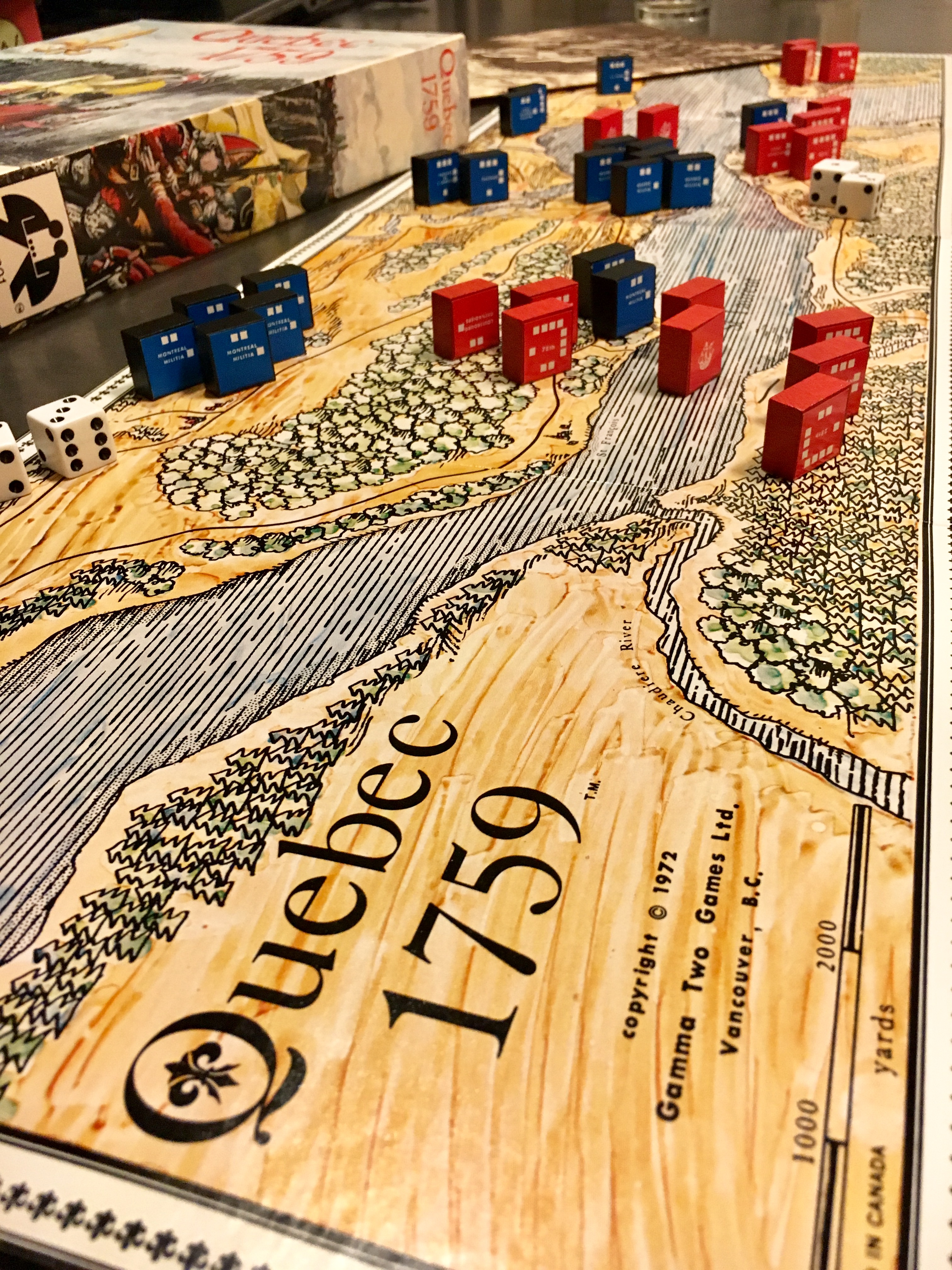

The games we play at MWG have also changed significantly. In its first decade, the club was almost exclusively home to historical miniatures gaming including Ancients, Hundred Years War, Napoleonic, American Civil War and World War II, all at multiple scales. Some board gaming from classic publishers like Avalon Hill and SPI also made regular appearances. Through the 1990s and into the 2000s, Warhammer Fantasy, Ancients and 40K rose to prominence, as did a greater interest in emerging Eurogames.

While miniatures, including WWII, ACW, French & Indian War, Robotech, Epic 40K, Star Wars: Legion and Marvel: Crisis Protocol, have been played recently, most of the club’s gaming interests have moved toward a focus on modern board games and wargames in the past 10 years. RPGs have also continued to have a small but consistent presence at the club throughout its history.

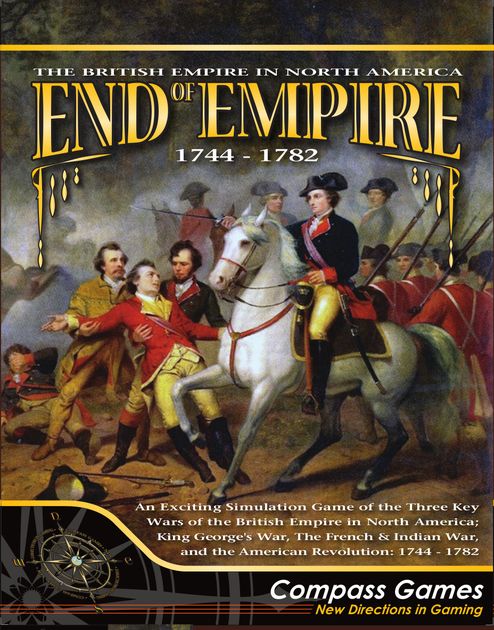

Over its history, MWG has also been an incubator for game design and playtesting. A number of our earliest members spent time at the offices of SPI here in NYC in the 70s and 80s playtesting now-classic games. The club has included prominent designers in its membership, including Adam Starkweather (IGS, MMP) and Carl Fung (SCS and BCS, MMP), newer designers like Mike Willner (Prelude to Revolution, Compass Games) and Mike Lorino (Seminal Catastrophe, Vuca Simulations), and GMT Games Art Director Justin Martinez.

Members have won multiple awards at regional Historical Miniatures Gaming Society (HMGS) conventions. And the club continues to host visitors from across the country and around the world. That has included gamers from Spain, the UK and Australia.

Running an organization like ours has not been without its challenges. We’ve had more than a couple floods, weathered some internal controversies, and survived an extended shutdown during the COVID-19 pandemic (during which time most members continued paying dues and we received a grant from HMGS to offset a financial shortfall). Most recently there has been some conversation about changing our name to Metropolitan Tabletop Gamers to potentially broaden our appeal, but we continue to see new people show up almost every week just as we are.

In 2024, Metropolitan Wargamers is celebrating its 40th anniversary. I’ve been fortunate to serve as President of MWG for the past ten years, and it remains one of the more unique communities of which I’ve been a part. The hobby, the city, the club, and its members have all changed over the years, but our core personality has remained intact as a community of dedicated gamers.

/pic2296647.jpg)